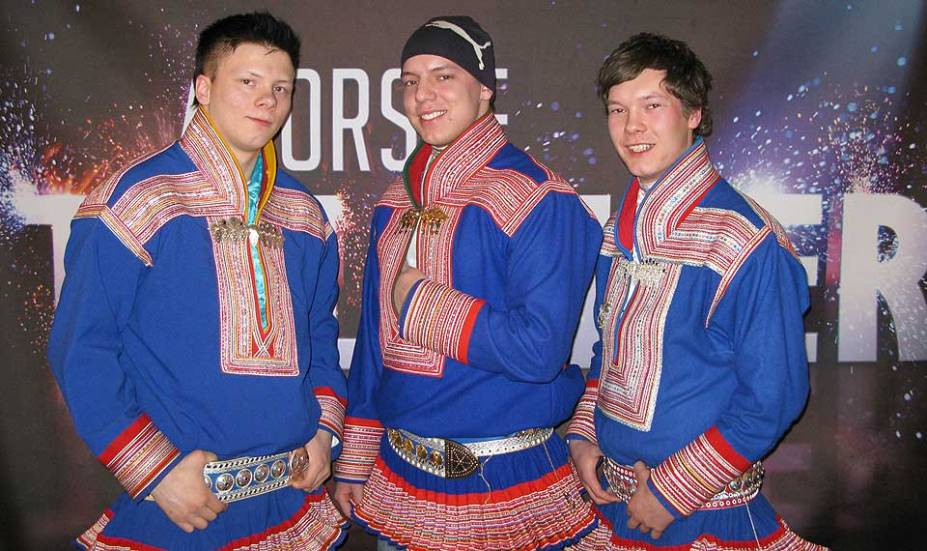

Islam: Sami or Saami people of the Sampi Region (Lapland) the Future Indigenous Muslims / Moslems and Potential Islamic State ISIS / ISIL or Daesh and Al Qaeda Terrorist Militants in Sweden, Finland and Norway in Scandinavia (Arctic), Baltics and Russia in Northern Europe

The Sami people (also Sámi or Saami, traditionally known in English as Lapps or Laplanders) are an indigenous Finno-Ugric people inhabiting the Arctic area of Sápmi, which today encompasses parts of far northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Kola Peninsula of Russia. The Sami are the only indigenous people of Scandinavia recognized and protected under the international conventions of indigenous peoples, and are hence the northernmost indigenous people of Europe.[8] Sami ancestral lands are not well-defined. Their traditional languages are the Sami languages and are classified as a branch of the Uralic language family.

| Sámit | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Total population | |

| 137,477 (est.) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 37,890–60,000[1][2] | |

| 30,000[3] | |

| 14,600–36,000[2][4] | |

| 9,350[5] | |

| 1,991[6] | |

| 136[7] | |

| Languages | |

| Sami languages (Akkala, Inari, Kildin, Kemi, Lule, Northern, Pite, Skolt, Ter, Southern, Ume) Russian, Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish |

|

| Religion | |

| Lutheranism (including Laestadianism), Eastern Orthodoxy, Sami shamanism, Conscious Atheism, non-adherence | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Finnic peoples | |

Etymologies

For more details on this topic, see Sápmi.

The Sámi are often known in other languages by the exonyms Lap, Lapp, or Laplanders. Some Sami regard these as pejorative terms,[11][12][13] while others do not.[13] Variants of the name Lapp

were originally used in Sweden and Finland and, through Swedish,

adopted by all major European languages: English: Lapps; German, Dutch: Lappen; Russian: лопари́ (lopari); Ukrainian: лопарі́; French: Lapons; Greek: Λάπωνες (Lápōnes); Hungarian: lappok; Italian: Lapponi; Polish: Lapończycy; Portuguese: Lapões; Spanish: Lapones; Romanian: laponi; Turkish: Lapon.

The first known historical mention of the Sami, naming them Fenni, was by Tacitus, about 98 A.D.[14] Variants of Finn or Fenni were in wide use in ancient times, judging from the names Fenni and Phinnoi in classical Roman and Greek works. Finn (or variants, such as skridfinn, “striding Finn”) was the name originally used by Norse speakers (and their proto-Norse speaking ancestors) to refer to the Sami, as attested in the Icelandic Eddas and Norse sagas (11th to 14th centuries). The etymology is somewhat uncertain, but the consensus seems to be that it is related to Old Norse finna, from proto-Germanic *finthanan (“to find”),[15] the logic being that the Sami, as hunter-gatherers “found” their food, rather than grew it. As Old Norse gradually developed into the separate Scandinavian languages, Swedes apparently took to using Finn exclusively to refer to inhabitants of Finland, while Sami came to be called Lapps. In Norway, however, Sami were still called Finns at least until the modern era (reflected in toponyms like Finnmark, Finnsnes, Finnfjord and Finnøy) and some Northern Norwegians will still occasionally use Finn to refer to Sami people, although the Sami themselves now consider this to be a pejorative term. Finnish immigrants to Northern Norway in the 18th and 19th centuries were referred to as “Kvens” to distinguish them from the Sami “Finns”. Ethnic Finns are a distinct group from Sami.

The word Lapp can be traced to Old Swedish lapper, Icelandic lappir (plural), probably of Finnish origin; compare Finnish lappalainen “Lapp”, Lappi “Lapland” (possibly meaning “wilderness in the north”); in older Finnish also lapp, the original meaning being unknown.[16][17] It is unknown how the word Lapp came into the Norse language, but one of the first written mentions of the term is in the Gesta Danorum by 12th-century Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus, who referred to the two Lappias, although he still referred to the Sami as (Skrid-)Finns.[18][19] In fact, Saxo never explicitly connects the Sami with the “two Laplands”. The term “Lapp” was popularized and became the standard terminology by the work of Johannes Schefferus, Acta Lapponica (1673), but was also used earlier by Olaus Magnus in his Description of the Northern people (1555). There is another suggestion that it originally meant “wilds”.

In Finland and Sweden, Lapp is common in place names, such as Lappi (Satakunta), Lappeenranta (South Karelia) and Lapinlahti (North Savo) in Finland; and Lapp (Stockholm County), Lappe (Södermanland) and Lappabo (Småland) in Sweden. As already mentioned, Finn is a common element in Norwegian (particularly Northern Norwegian) place names, whereas Lapp is exceedingly rare.

In the North Sámi language, láhppon olmmoš means a person who is lost (from the verb láhppot, to get lost).

Homeland of the Sámi people

Terminological issues in Finnish are somewhat different. Finns living in Finnish Lapland generally call themselves lappilainen, whereas the similar word for the Sámi people is lappalainen. This can be confusing for foreign visitors because of the similar lives Finns and Sámi people live today in Lapland. Lappalainen is also a common family name in Finland. As in the Scandinavian languages, lappalainen is often considered archaic or pejorative, and saamelainen is used instead, at least in official contexts.

History

Main article: Sami history

A Sami family in Norway around 1900

Petroglyphs and archeological findings such as settlements dating from about 10,000 B.C. can be found in the traditional lands of the Sami.[26] The now-obsolete term for the archaeological culture of these hunters and gatherers of the late Paleolithic and early Mesolithic is Komsa. A cultural continuity between these stone-age people and the Sami can be assumed due to evidence such as the similarities in the decoration patterns of archeological bone objects and Sami decoration patterns, and there is no archeological evidence of this population being replaced by another.[26]

Recent[when?] archaeological discoveries in Finnish Lapland were originally seen as the continental version of the Komsa culture about the same age as the earliest finds on the coast of Norway.[27][28] It is hypothesized that the Komsa followed receding glaciers inland from the Arctic coast at the end of the last ice age (between 11,000 and 8000 years B.C.) as new land opened up for settlement (e.g., modern Finnmark area in the northeast, to the coast of the Kola Peninsula).[29] Since the Sami are the earliest ethnic group in the area, they are consequently considered an indigenous population of the area.[30]

Southern Limits of Sami Settlement in the Past

A Sami man and child in Finnmark, Norway, circa 1900

Origins of the Norwegian Sea Sami

The bubonic plague

Sami people, in Norway, 1928

Nordic Sami people, Lavvu circa 1900

This social economic balance greatly changed with the introduction of the bubonic plague to northern Norway in December 1349. The Norwegians were closely connected to the greater European trade routes, along which the plague traveled; consequently, they were infected and died at a far higher rate than Sami in the interior. Of all the states in the region, Norway suffered the most from this plague.[37] Depending on the parish, sixty to seventy-six percent of the northern Norwegian farms were abandoned following the plague,[38] while land-rents, another possible measure of the population numbers, dropped down to between 9–28% of pre-plague rents.[39] Although the population of northern Norway is sparse compared to southern Europe, the spread of the disease was just as rapid.[40] The method of movement of the plague-infested flea (Xenopsylla cheopsis) from the south was in wooden barrels holding wheat, rye, or wool—where the fleas could live, and even reproduce, for several months at a time.[41] The Sami, having a non-wheat or –rye diet, eating fish and reindeer meat, living in communities detached from the Norwegians, and being only weakly connected to the European trade routes, fared far better than the Norwegians.[42]

Fishing industry

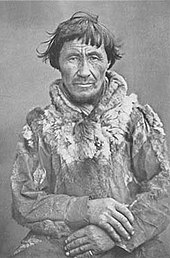

A Sea Sami man from Norway by Prince Roland Bonaparte in 1884

A Sea Sami man from Norway by Prince Roland Bonaparte in 1884

Mountain Sami

As the Sea Sami settled along Norway’s fjords and inland waterways pursuing a combination of farming, cattle raising, trapping and fishing, the smaller minority of the Mountain Sami continued to hunt wild reindeer. Around 1500, they started to tame these animals into herding groups, becoming the well-known reindeer nomads, often portrayed by outsiders as following the archetypal Sami lifestyle. The Mountain Sami faced the fact that they had to pay taxes to three nation-states, Norway, Sweden and Russia, as they crossed the borders of each of the respective countries following the annual reindeer migrations, which caused much resentment over the years.[50] Sweden made the Sami work in a slavemine at Nasafjäll, causing many Samis to flee from the area, so a large part of the provinces previously used by Pite and Lule Samis is depopulated. Government troops were ordered to prevent the Sami from fleeing.[50]

Traditional raised Sami storehouse, displayed at Skansen, Stockholm. A similar structure, is mentioned in Russian fairy tales as a “house with chicken legs”

Post-1800s

| This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

However, during the 19th century, Norwegian authorities pressured the Sami to make Norwegian language and culture universal. Strong economic development of the north also ensued, giving Norwegian culture and language higher status. On the Swedish and Finnish sides, the authorities were less militant, although the Sami language was forbidden in schools and strong economic development in the north led to weakened cultural and economic status for the Sami. From 1913 to 1920, the Swedish race-segregation political movement created a race-based biological institute that collected research material from living people and graves, and sterilized Sami women. Throughout history, Swedish settlers were encouraged to move to the northern regions through incentives such as land and water rights, tax allowances, and military exemptions.[51]

The strongest pressure took place from around 1900 to 1940, when Norway invested considerable money and effort to wipe out Sami culture. Anyone who wanted to buy or lease state lands for agriculture in Finnmark had to prove knowledge of the Norwegian language and had to register with a Norwegian name. This caused the dislocation of Sami people in the 1920s, which increased the gap between local Sami groups (something still present today) that sometimes has the character of an internal Sami ethnic conflict. In 1913, the Norwegian parliament passed a bill on “native act land” to allocate the best and most useful lands to Norwegian settlers. Another factor was the scorched earth policy conducted by the German army, resulting in heavy war destruction in northern Finland and northern Norway in 1944–45, destroying all existing houses, or kota, and visible traces of Sami culture. After World War II the pressure was relaxed though the legacy was evident into recent times, such as the 1970s law limiting the size of any house Sami people were allowed to build.[citation needed]

The controversy around the construction of the hydro-electric power station in Alta in 1979 brought Sami rights onto the political agenda. In August 1986, the national anthem (“Sámi soga lávlla“) and flag (Sami flag) of the Sami people were created. In 1989, the first Sami parliament in Norway was elected. In 2005, the Finnmark Act was passed in the Norwegian parliament giving the Sami parliament and the Finnmark Provincial council a joint responsibility of administering the land areas previously considered state property. These areas (96% of the provincial area), which have always been used primarily by the Sami, now belong officially to the people of the province, whether Sami or Norwegian, and not to the Norwegian state.

Contemporary

The indigenous Sami population is a mostly urbanised demographic, but a substantial number live in villages in the high arctic. The Sami are still coping with the cultural consequences of language and culture loss related to generations of Sami children taken to missionary and/or state-run boarding schools and the legacy of laws that were created to deny the Sami rights (e.g., to their beliefs, language, land and to the practice of traditional livelihoods). The Sami are experiencing cultural and environmental threats,[23] including oil exploration, mining, dam building, logging, climate change, military bombing ranges, tourism and commercial development.

Vindelfjällen

- Natural-resource prospecting

- Mining

- Logging

- Military activities

- Land rights

Suorvajaure near Piteå

- Water rights

The Sami recently stopped a water-prospecting venture that threatened to turn an ancient sacred site and natural spring called Suttesaja into a large-scale water-bottling plant for the world market—without notification or consultation with the local Sami people, who make up 70 percent of the population. The Finnish National Board of Antiquities has registered the area as a heritage site of cultural and historical significance, and the stream itself is part of the Deatnu/Tana watershed, which is home to Europe’s largest salmon river, an important source of Sami livelihood.[63]

In Norway, government plans for the construction of a hydroelectric power plant in the Alta river in Finnmark in northern Norway led to a political controversy and the rallying of the Sami popular movement in the late 1970s and early 1980s. As a result, the opposition in the Alta controversy brought attention not only to environmental issues but also to the issue of Sami rights.

- Climate change and environment

Sami man from Norway

The 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster caused nuclear fallout in the sensitive Arctic ecosystems and poisoned fish, meat[65] and berries. Lichens and mosses are two of the main forms of vegetation in the Arctic and are highly susceptible to airborne pollutants and heavy metals. Since many do not have roots, they absorb nutrients, and toxic compounds, through their leaves. The lichens accumulated airborne radiation, and 73,000 reindeer had to be destroyed as “unfit” for human consumption in Sweden alone. The government promised Sami indemnification, which was not acted upon by government.

Radioactive wastes and spent nuclear fuel have been stored in the waters off the Kola Peninsula, including locations that are only “two kilometers” from places where Sami live. There are a minimum of five “dumps” where spent nuclear fuel and other radioactive waste are being deposited in the Kola Peninsula, often with little concern for the surrounding environment or population.[66]

- Tourism

Discrimination against the Sami

Three Sami women

Norway has been greatly criticized by the international community for the politics of Norwegianization of and discrimination against the aboriginal population of the country.[70] On 8 April 2011, the UN Racial Discrimination Committee recommendations were handed over to Norway; these addressed many issues, including the educational situation for students needing bilingual education in Sami. One committee recommendation was that no language be allowed to be a basis for discrimination in the Norwegian anti-discrimination laws, and it recommended wording of Racial Discrimination Convention Article 1 contained in the Act. Further points of recommendation concerning the Sami population in Norway included the incorporation of the racial Convention through the Human Rights Act, improving the availability and quality of interpreter services, and equality of the civil Ombudsman’s recommendations for action. A new present status report was to have been ready by the end of 2012.[71]

Even in Finland, where Sami children, like all Finnish children, are entitled to day care and language instruction in their own language, the Finnish government has denied funding for these rights in most of the country, including even in Rovaniemi, the largest municipality in Finnish Lapland. Sami activists have pushed for nationwide application of these basic rights.[72]

As in the other countries claiming sovereignty over Sami lands, Sami activists’ efforts in Finland in the 20th century achieved limited government recognition of the Samis’ rights as a recognized minority, but the Finnish government has clung unyieldingly to its legally enforced premise that the Sami must “prove” their land ownership, an idea incompatible with and antithetical to the traditional reindeer-herding Sami way of life. This has effectively allowed the Finnish government to take without compensation, motivated by economic gain, land occupied by the Sami for centuries.[73]

Sami groups and languages

Main article: Sami languages

American scientist Michael E. Krauss published in 1997 an estimate of Sami population and their languages.[113][114]| Group | Population | Language group | Language | Speakers | % | Most important territory | Other traditional territories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Sami | 42 500 | Western Sami languages | Northern Sami language | 21 700 | 51% | Norway | Sweden, Finland |

| Lule Sami | 8 000 | Western Sami languages | Lule Sami language | 2 300 | 29% | Sweden | Norway |

| Pite Sami | 2 000 | Western Sami languages | Pite Sami language | 60 | 3% | Sweden | Norway |

| Southern Sami | 1 200 | Western Sami languages | Southern Sami language | 600 | 50% | Sweden | Norway |

| Ume Sami | 1 000 | Western Sami languages | Ume Sami language | 50 | 5% | Sweden | Norway |

| Skolt Sami | 1 000 | Eastern Sami languages | Skolt Sami language | 430 | 43% | Finland | Russia, Norway |

| Kildin Sami | 1 000 | Eastern Sami languages | Kildin Sami language | 650 | 65% | Russia | |

| Inari Sami | 900 | Eastern Sami languages | Inari Sami language | 300 | 33% | Finland | |

| Ter Sami | 400 | Eastern Sami languages | Ter Sami language | 8 | 2% | Russia | |

| Akkala Sami | 100 | Eastern Sami languages | Akkala Sami language | 7 | 7% | Russia | |

| Sami | 58 100 | Sami languages | Sami languages | 26 105 | 45% | Norway | Sweden, Finland, Russia |

Geographic distribution of the Sami languages:

Darkened area represents municipalities that recognize Sami as an official language.

- Southern Sami

- Ume Sami

- Pite Sami

- Lule Sami

- Northern Sami

- Skolt Sami

- Inari Sami

- Kildin Sami

- Ter Sami

- Northern Sami language (Davvisámegiella): 30,000 (definitely endangered)

- Lule Sami language (Julevsámegiella): 2,000 (severely endangered)

- Kildin Sami language (Кīlt sam’ kīll): 787 (severely endangered)

- Southern Sami language (Åarjelsaemien gïele): 500 (severely endangered)

- Skolt Sami language (Nuõrttsää’mǩiõll): 300 (severely endangered)

- Inari Sami language (Anarâškielâ): 400 (severely endangered)

- Ume Sami language (Ubmejensámiengiella): 20 (critically endangered)

- Pite Sami language (Bidumsámegiella): 20 (critically endangered)

- Ter Sami language (Ter saa’me kiill): 2 (critically endangered)

- Akkala Sami language: 0 (extinct)

Many Sami do not speak any of the Sami languages any more due to historical assimilation policies, so the number of Sami living in each area is much higher.

As with many indigenous languages,[116] all Sami languages are at some degree of endangerment, ranging from what UNESCO defines as “definitely endangered” to “extinct”.[115]

Division by geography

Sápmi is traditionally divided into:- Eastern Sapmi (Inari, Skolt, Akkala, Kildin and Teri Sami in Kola peninsula (Russia) and Inari (Finland, formerly also in eastern Norway)

- Northern Sápmi (Northern, Lule and Pite Sami in most of northern parts of Norway, Sweden and Finland)

- Southern Sápmi (Ume and Southern Sami in central parts of Sweden and Norway)

Division by occupation

A division often used in Northern Sami is based on occupation and the area of living. This division is also used in many historical texts:[117]- Reindeer Sami or Mountain Sami (in Northern Sami boazosapmelash or badjeolmmosh). Previously nomadic Sami living as reindeer herders. Now most have a permanent residence in the Sami core areas. Some 10% of Sami practice reindeer herding, which is seen as a fundamental part of a Sami culture and, in some parts of the Nordic countries, can only be practiced by Samis.

- Sea Sami (in Northern Sami mearasapmelash). These lived traditionally by combining fishing and small-scale farming. Today, often used for all Sami from the coast regardless of their occupation.

- Forest Sami who traditionally lived by combining fishing in inland rivers and lakes with small-scale reindeer-herding.

- City Sami who are now probably the largest group of Sami.

Division by country

According to the Norwegian Sami Parliament, the Sami population of Norway is 40,000. If all people who speak Sami or have a parent, grandparent, or great-grandparent who speaks or spoke Sami are included, the number reaches 70,000. As of 2005, 12,538 people were registered to vote in the election for the Sami Parliament in Norway.[citation needed] The bulk of the Sami live in Finnmark and Northern Troms, but there are also Sami populations in Southern Troms, Nordland and Trøndelag. Due to recent migration, it has also been claimed that Oslo is the municipality with the largest Sami population. The Sami are in a majority only in the municipalities of Guovdageaidnu-Kautokeino, Karasjohka-Karasjok, Porsanger, Deatnu-Tana and Unjargga-Nesseby in Finnmark, and Gáivuotna (Kåfjord) in Northern Troms. This area is also known as the Sami core area. Sami and Norwegian are equal as administrative languages in this area.In Sweden and Norway, Sami are primarily Lutheran, in Finland and Russia they are orthodox Christians.

According to the Swedish Sami Parliament, the Sami population of Sweden is about 20,000.

According to the Finnish Population Registry Center and the Finnish Sami Parliament, the Sami population living in Finland was 7,371 in 2003.[118] As of 31 December 2006, only 1776 of them had registered to speak one of the Sami languages as the mother tongue.[119]

According to the 2002 census, the Sami population of Russia was 1,991.

Since 1926, the number of identified Sami in Russia has gradually increased:

- Census 1926: 1,720 (this number refers to the entire Soviet Union)

- Census 1939: 1,829

- Census 1959: 1,760

- Census 1970: 1,836

- Census 1979: 1,775

- Census 1989: 1,835

- Census 2002: 1,991

Sami immigration outside of Sapmi

Reindeer in Alaska

Descendants of these Sami immigrants typically know little of their heritage, because their ancestors purposely hid their indigenous culture to avoid discrimination from the dominating Scandinavian or Nordic culture. Though some of these Sami are diaspora that moved to North America in order to escape assimilation policies in their home countries, many continued to downplay their Sami culture in an internalization of colonial viewpoints about indigenous peoples and in order for them to try to blend into their respective Nordic cultures. There were also several Sami families that were brought to North America with herds of reindeer by the U.S. and Canadian governments as part of the “Reindeer Project” designed to teach the Inuit about reindeer herding.[121] There is a long history of Sami in Alaska.

Some of these Sami immigrants and descendants of immigrants are members of the Sami Siida of North America.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.